Health care is not a business sector that has responded well to economic principles; it is not freely traded among educated buyers and sellers, and is highly regulated by both federal and state governments. In addition, the U.S. healthcare reimbursement methodology has not historically rewarded business efficiency; in fact, reimbursements have incented inefficiency, waste, and even error by paying on a “per piece” manufacturing model. For the past generation, as technological advances have boomed across virtually all other business sectors, which are relatively free to innovate and incentivize to lower costs through operational efficiencies, it has taken a series of dedicated policy steps to bring technological transformation to health information management.

The year 1999 saw the dot-com boom, the NASDAQ hitting 5,000 (a level not seen again until 15 years later), the emergence of Silicon Valley as an economic engine, and the rise of personal computers; at the same time, at least 44,000 people – and perhaps as many as 98,000 – died in hospitals each year as a result of medical errors. The Institute of Medicine convened a study to address the question of why health care was still predominantly using paper-based records when so many new computer-based technologies were emerging. The focus of the study was on quality, with the belief that the tools existed to improve it, and two major conclusions were drawn: 1) that the computer-based patient record (CPR) was an essential technology for health care, and 2) that there was no coordination, national champion, or leadership for CPRs. With this as a foundation, the loM laid out a comprehensive strategy to reduce preventable medical errors through CPRs, setting a goal of a minimum 50% reduction over the following five years.

Consumerization – a major driver of technological innovation – had not yet taken root in health care in the early 2000s (and I would argue that, for the most part, we still do not have a consumer-driven health system today); instead, the driver of technological innovation in health care was federal policy and the payments that were a major part of that policy. With the presidency of George W. Bush, we found that there was a fairly classic republic philosophy-driven approach of limited government mandates and “pump priming” through pilot projects and private/public partnerships. There was also recognition from those of us in the private sector that we had a very big problem with lack of standardization; much like the early days of railroads when different companies and regions used different track gauges, there was limited or no exchange between competing health information systems – what we today call “interoperability.”

HIMSS is not a traditional “interest group,” as we do not represent the business interests of IT vendors or hospitals; instead, our mission is to improve health through IT. As a result, although vendors and providers found a business advantage in proprietary products and proprietary ownership of data, we did not endorse that; rather, we set out to partner with the federal government to drive IT adoption. In 2002, HIMSS’s strategic recommendation was that by 2010, 85% of healthcare systems and 50% of physician practices should have an EHR that included at least half of the HIMSS-endorsed EHR attributes.

In President Bush’s January 20, 2004 State of the Union Address, he stated, “By computerizing health records, we can avoid dangerous medical mistakes, reduce costs, and improve care.” At the time, we did not have a grand, comprehensive strategy or worldview, but this was truly the start of a governmental process that would ultimately funnel more than $40 billion in federal dollars toward the computerization of health information technology. (Later in 2004, the Bush administration formed the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, which became – and remains – the focal point for federal HIT policy.)

In September of 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit- a crisis of epic proportions that resulted in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, the flooding of hospitals, and the loss of paper records. The federal government began a pilot test of an EHR database with at least partial information for 80% of the population in hurricane-affected areas. Dr. David Brailer, the first national coordinator for health IT stated, “We don’t want people to be saved, taken to a shelter, and then face the risk of death because doctors don’t know what’s going on with them.” Then-Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich commented, “Paper kills. Paper records are an utterly irrational national security risk. I hope we will never have a more vivid, more explicit case study in the need to have electronic health records now.”

As noted before, GOP philosophy impacted the policy response. The Republic administration was not going to mandate more federal government intervention, implement significant new regulations, or fund large government spending projects on the matter. Throughout this period, federal officials spoke about their vision of change, but counted on others to create and implement, with an emphasis placed on private enterprise driving change. Associations, too, played a large role, primarily HIMSS and AHIMA.

The first of two voluntary groups was formed in 2004 – the Certification Commission for Health Information Technology (CCHIT) – with support from three leading industry associations in healthcare information management and technology: AHIMA, HIMSS, and the National Alliance for Health Information Technology. A nonprofit 501(c)3 organization, CCHIT’s mission was to accelerate the adoption of robust, interoperable health IT and to address the fear that the market would not know how to select EHRs by creating an objective, repeatable inspection and certification process. This was a voluntary effort that began with no funding, and was an open, transparent development process involving more than 200 volunteers and multiple cycles of public comment.

The second group created was the Healthcare Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP), founded in October of 2005 under a contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Panel is overseen by the American National Standards Institute in collaboration with strategic partners including HIMSS, Advanced Technology Institute, and Boaz Allen Hamilton. Driven by federal talk and fueled by professional commitment, HITSP was created to resolve product challenges such as data exchange, data propriety, continuity of care, and reduction of error. It was a consensus-based process with 687 member organizations and 644 individual participants that delivered interoperability specifications and became the central point for collaboration amongst vendors, providers, and the government to address lack of standards and interoperability.

Toward the end of the George W. Bush era, a second crisis hit – the Great Recession. The U.S. economy shrank by nearly 4%, the largest year-over-year decline since World War II and the worst of any modern recession. With widespread failures in financial regulation, dramatic breakdowns in corporate governance, an explosive mix of excessive borrowing and risk by households and Wall Street, key policy makers who were ill-prepared for the crisis, and systemic breaches in accountability and ethics at all levels, the Great Recession presented incoming president Barack Obama with a “must address” crisis and “must pass” legislative opportunity. In addition to economic stimulus provisions, his American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was used as an opportunity to pass policy initiatives in education, energy, and health care; I hypothesize that the HITECH Act within ARRA was the most significant driver of this era in transforming America’s healthcare information from paper to digital, as it included incentives to aid in the development of a robust IT infrastructure for health care and to assist providers and other entities in adopting and using health IT.

From President Obama’s earliest days, he identified health care as one of his signature policy initiatives, and, specifically, how technology could drive improvement. In 2009, the president-elect stated, “To improve the quality of our health care while lowering its cost, we will make the immediate investments necessary to ensure that within five years, all Americans’ medical records are computerized. This will cut waste, eliminate red tape, and reduce the need to repeat expensive medical tests.” In contrast to the Republication philosophy, the Democratic approach was built on large government-funded and -operated programs. Significant new regulatory authority was implemented, and bureaucracy designed the plan with limited outside influence, as there was a perceived failure of the private sector to invest and to create the right products. The federal government’s stance was that only with funding incentives would change happen; that the government needed to step in to establish minimum requirements for functionality, interoperability, and reporting; and that technologies should be mandated by linking product certification, demonstrated use, and payments. The goal was to employ EH Rs to drive quality up and cost down – not simply to get technology to physicians. The administration started with a fairly comprehensive vision to be implemented in stages, starting with the digitization of data; coupled with advanced clinical processes, this would lead to improved outcomes and eventually to expanded access.

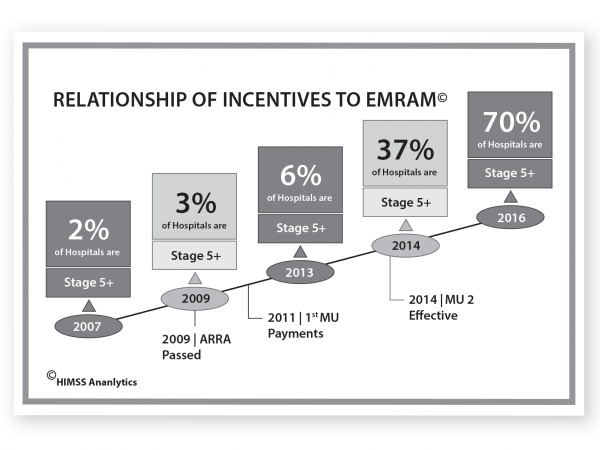

Passed just 30 days after Obama’s inauguration, the “must pass” legislation contained more than $800 billion of new federal spending, including requirements that providers do certain things electronically in order to qualify for incentive payments, such as electronic prescribing, computerized practitioner order entry, clinical documentation, and clinical decision support. The illustration at left demonstrates the impact of meaningful use (MU) incentives on the adoption of EMRs, Stage 5 roughly equating to the installment requirements of meaningful use – the regulatory definition to receive ARRA payments.

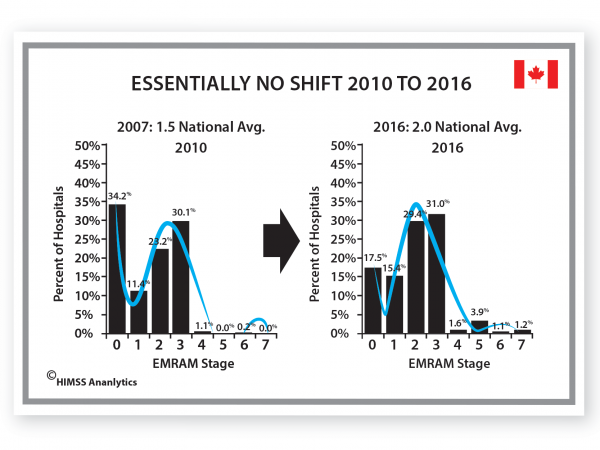

But we still might question whether these two factors-change in health policy and change in HIT adoption – are related, so let’s quickly look at a country comparison to see if we can build the case more strongly. U.S. and Canadian markets have the same vendors, and both countries had similar HIT adoption rates in 2007; the differences between the two countries’ health systems were mainly related to access and financing. In neither system was there a mechanism for direct payments to providers for the adoption and use of HIT prior to the passage of ARRA in the U.S. in 2009, but both have had a significant federal-level policy focus on HIT adoption and use over the past 10-15 years.

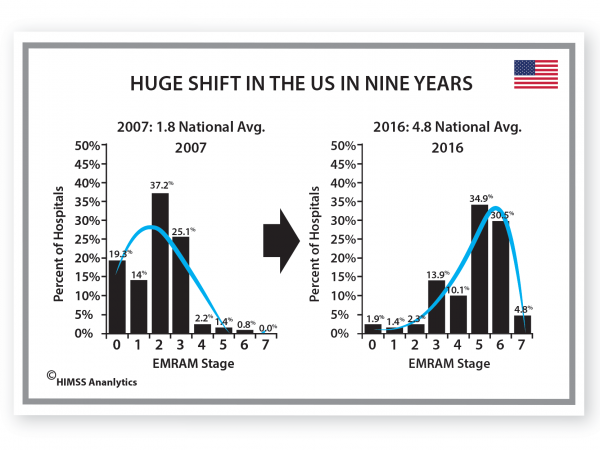

In the U.S., we have seen a dramatic shift in the EMRAM (EMR Adoption Model) scoring – this chart demonstrates that the mode shifted from Stage 2 to Stage 5, and the average from Stage 1.8 to Stage 4.8 during the period of incentive payments, and continues to climb. Today, 98% of eligible hospitals across the country have successfully demonstrated meaningful use.

By contrast, Canada, during the same period, saw very little change; its national EMRAM stage average has only moved from 1.5 to 2.0, and the distribution has remained largely the same – skewed more to the lower stages. Although there are limited examples of higher tech use, there has been no fundamental shift.

Based on the data, and on analysis of the historical environment, I see a very strong correlation, if not an actual cause and effect relationship between changes in policy and increases in HIT adoption. Federal policy continues to shape and influence health care; universal access, mandated coverage, and Medicare for all are part of the next story.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

H. Stephen “Steve” Lieber is Of Counsel to Quick Leonard Kieffer. Prior to joining QLK, Steve spent 17 years as the president and CEO of HIMSS, the leading global, cause-based, not-for-profit organization focused on better health through information and technology.